CONFLICT ZONE DK: Are we doing enough to protect our wildlife?

CONFLICT ZONE DK: Are we doing enough to protect our wildlife?

Mangalore Today News Network

By Mahesh Nayak

Mangaluru, Sept 30, 2015: There is a worn out phrase in these parts, which in Kannada goes: ‘Aparoopada Athithi’. It literally means ‘Uncommon Guest’ and when appearing as a newspaper headline, it light heartedly refers to an unwelcome guest of the animal kind. Should a wild animal like a leopard or an elephant or a crocodile show up uninvited into anyone’s house, the poor would-be hosts will scream for dear life and a media circus naturally follows. In such cases, the headline the next day would invariably read: “Aparoopada Athithi shows up at such and such a place.”

This familiar scenario also highlights the predicament facing those dealing with wildlife issues these days. Every few days, yet another incidence of a wild animal’s incursion into human territory takes place and it sparks off a mass frenzy among the people of the affected locality. Politicians shoot off their mouths and commoners scream demands. Kill the beast, it could be a man eater. No, trap the poor animal and give it to the zoo. How mean!! Animals are free spirited, set it free somewhere safe…

So have all the animals of the jungle ganged up and declared war on humankind? Are these the suicide bombers dispatched by the Maharaja of the jungle to deliver a strong message to humans? “No,” self styled eco-lovers will love to say, “You’ve destroyed their home, so now pay the price.” As pop explanation goes, the animals are being pressured by ‘habitat loss’ to turn on humans out of sheer desperation. We have to solve this by growing more forests and give the animals their space. But is the issue really that simple? Or are there more angles to this than one would ordinarily assume?

These are the very questions that the workshop on ‘Dealing with leopards and elephants in human use landscapes’ sought to answer when it was held in the city recently. Organized by Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), India Program in co-operation with Mangalore Press Club and DK Working Journalists Union, this was part of the recent initiatives of WCS to sensitize the media about wildlife interventions and reshape public perception of wildlife management. Among the resource person who shared their expertise during the workshop were Dr Vidya Athreya, a Pune based conservationist and a research fellow working with WCS and Virat Singh, a Mumbai based journalist who has reported extensively on wildlife issues.

Dr Vidya Athreya speaking at the workshop in Mangaluru

Like the much clichéd theory of ‘clash of civilizations’, the idea of ‘human-wildlife conflict’ too has captured public imagination in recent years and entered the collective psyche in a big way. Increasing incidences of wild animals trespassing into human settlements, incidences of apparent attacks on humans, loss of life and property are being reported with alarming regularity and the debate in the media finally settles down to the issue of ‘human-wildlife conflict’.

However more discerning spokes-persons for the cause now prefer the more progressive term ‘human-wildlife interaction’ and further narrow down to ‘interactions having negative impact on one or both entities’. But Dr Vidya Athreya takes pains to clarify that the idea of ‘human-wildlife conflict’ is a human dilemma, which does not bother the animals in any way. “Animals do not recognize man made boundaries and maps. The dichotomy that people should live in towns and animals should live in the jungle exists only in minds of human and not theirs. Animals live only by their instincts,” she says.

She should know better. After all she has spent the better part of her life working with wildlife and is an acknowledged expert on leopards. As she implies, it is also foolish to categorize all animals under one brand called ‘wildlife’. “Every wild animal is a different species altogether and it has its own reason for coming to town. The right way to deal with it should be to study the animal scientifically and come up with solutions that meet both animal needs and human needs,” she says.

According to her human-wildlife interface is nothing new and has always been a part of life. In the course of evolution humans have learned to live with wild animals and devised ways to co-exist without hurting each other’s interests. “There is a lot of traditional wisdom even now in practice in rural areas which are meant to minimize negative impact from interaction with wildlife. Nobody has done any research into this, so we are unaware of such measures,” she explains. “Indentifying such practices and reviving them would be a good idea to solve many of the present day problems haunting us.”

Indeed the increase in so-called incidences of ‘human-wildlife conflict’ could be just illusory. True, destruction of habitat is rampant in our country and forests are disappearing faster than the blink of the eye. The list of species waiting on the death row of extinction too is growing at an alarming rate. But this is an altogether different matter and not to be confused with the so-called ‘conflict’. While habitat loss call for conservation measures as a solution, conflict essentially has to do with management of relationship between humans and wildlife. As Dr. Vidya Athreya points out, this issue – of sharing of space by humans and animals - has been alive from time immemorial and humans have adjusted to the situation in their own ways as their contemporary common community wisdom dictated. Animals living on the periphery of the jungle would always have had a tendency to go across for a walk. Leopards, elephants and monkeys are the most common wild animals which humans tend to have problems with. Our district has few monkeys, but the awesome king cobras are nowadays being increasingly sighted outside their natural homes deep in the Western Ghats.

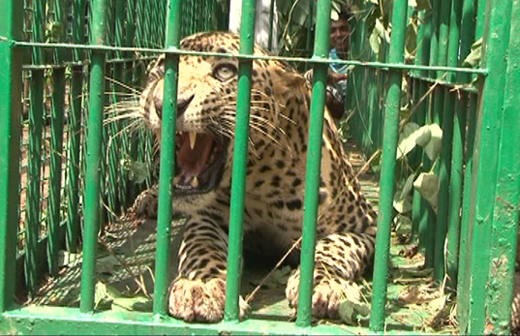

In earlier days, if people sighted a wild animal in their land, they either did not bother as they were used to the phenomenon or it was simply chased away. No one would have given it a second thought. Not so now. Today such an eventuality would be ‘Breaking News’ and guarantee instant media stardom for the intruder, attract scores of wildlife ‘experts’ with tons of advice and finally end up as an elaborate entrapment operation to ‘rescue and rehabilitate / release’ the delinquent beast. In worst case scenarios, villagers might attack and kill the animal. Sometimes leopards meet a cruel fate when they get trapped in snares laid by villagers to hunt pigs. Angry villagers are known to avenge trouble causing leopards with poisoned bait too.

Except in instances when the animal has to be physically lifted out of a well or some such precarious position, in most cases the ‘rescue’ of the beast would be a futile operation. The first question to ask would be: ‘rescuing’ from what? In many cases the animal is needless injured in the process of trapping it and will also fail to acclimatize in the new habitat where it is released. Giving the example of leopards in which she has the required expertise, Dr Vidya says leopards have always shared space with humans. “In India more leopards are found in human use landscapes than in protected habitats. They live in thickets, groves, shrub land and in sugarcane fields,” she explains.

Hence there seems to be no real conflict. Leopards are smaller than tigers and are highly adaptable. They lie low during the day and hunt at night. They have taken a liking for hunting domestic dogs and this is what attracts them to human habitats, apart from the lure of other small animals like goats and pigs. Leopards are very shy, not aggressive by nature and general stay away from humans. Attacks happen only when they are provoked and cornered. If they are left alone, you wouldn’t even know their presence in your neighbourhood. Hence the best way to deal with leopards, says Dr. Athreya, is to learn to live with them. If we take measures to protect ourselves and our belongings, then leopards won’t harm us in any way, she says. These measures could be to keep dogs in their kennels and livestock in well protected sheds at night. Cleaning up litter and clearing up garbage in your vicinity, which attract dogs would be another good preventive measure. Building toilets instead of using the bushes for the purpose and not letting out kids into the open (as leopards sometimes confuse them for dogs) are also a good way of keeping leopards at bay. Protect what is yours and the leopards will take care of themselves, seems to be the conservation logic.

The issue of ‘conflict’ usually raises its head only when the animal is discovered in human use environments. In such cases, the best way to deal with them is to let them be. Given a chance, leopards escape quietly, though elephants may not be so obliging. They are the masters of their universe and take their own sweet time to go their way. For them the best way would be to monitor their movement (as the herd adopts a ‘corridor’ for transit between larger habitats) and take preventive measures to block their entry into your space. This could mean putting up an electrified fence around your farm (and not the jungle which would be again impossibly foolish) or digging trenches deep enough to dissuade them from coming your way. “A sound understanding of animal behaviour should be the basis for solving problems relating to wildlife,” says Niren Jain, Co-ordinator of Kudremukh Wildlife Foundation who has worked extensively in this field.

Capturing and relocating wild animals, though it makes ample sense to lay people, does not really help in any way, says Dr. Athreya. It actually worsens the situation as the relocated animal gets disoriented and becomes potentially dangerous, she says. There could be other angles too. Leopards for instance are highly territorial and removing one from its territory would only create a vacuum which other leopards in the neighborhood will automatically fill. Hence co-ordination between police, forest department, conservationists and media is very important in dealing with the issue, she adds.

Agrees Virat Singh, a Mumbai based journalist who accompanied her: “Media can help in molding public perception of wildlife. Instead to feeding sensational negative perception of wild animals, media should interact with forest department and wildlife experts and try to balance the news with truth, human concerns and wildlife concerns. Media can also pick on problems and bottlenecks in wildlife management and highlight them. This will put pressure on decision makers and help the public.”

However rescuing wild animals brings no joy to the rescuer either. Pilikula Nisarga Dhama is the main rescue and rehabilitation centre for wild animals in the region. Says Prabhakar Sharma, its Executive Director: “Every year we deal with 8-10 leopard rescues. Though we release most of them into the wild, in some cases it is not possible as the animal could be permanently injured or it might have been brought in when it was too young and would not know how to live on its own. Hence there is a need to have a full fledged rescue and rehabilitation unit with all facilities for caring of such animals.”

Hence it is time for the authorities, wildlife experts and other stakeholders involved to put their act together and evolve a long lasting strategy for the effective management of human-wildlife interface in this region.

- Need For ‘Students, Alcohol and Drugs’ survey

- New Synthetic Drugs Trapping Youth

- Mood Modifying Chips - Future of Drug Use

- Ramping up Indo-Bangla border security

- IITM- A premier educational Institution in a forest. What can we learn?

- Former PM, Manmohan Singh: Notable laws passed under his tenure

- Hashish on Ratnagiri Seashore

- The Poor cry out to Us: Do we respond?

- Clandestine Meth Labs Sprouting Across India

- Hydro ganja from Bangkok latest craze among youth in India

- "Memories to Treasure" Dr.Michael Lobo’s new book

- Dominance of Private Universities: Will it make education inaccessible to underprivileged students?

- Monti Phest: A rich heritage of South Canara

- Kashmir Bhavan in Bengaluru: A must visit place

- "MAI and I" Book of Angelic Emotions

- Draupadi Murmu - The New ’President of India’

- Anthony Ashram in the city grows a classic museum

- First College of Fisheries in India - A Golden Jubilarian

- Flushing Meadows - A Vintage Mansion

- The Colonel�s Bequest

- A Mangalorean PM and his RBI Governor Brother: The Extraordinary story of the Benegal Brothers

- There is no higher religion than Truth: Theosophical Society

- L�affaire - Ashu & Yiju of Mangalore

- Mangalore in Kowloon

- 1568 to 2018 AD: 450 years of Christianity in Mangaluru

- Vice President elect Naidu moves on from nadir to zenith, the phenomenal journey

- Embracing the Outdoors: How Heated Jackets Are Revolutionizing Cold Weather Activities

- Efficient and Sustainable Packaging Solutions with FIBCs

- The Hybrid Kilt Revolution | Where Tradition Gets Trendy

- Affordable Elegance | Embrace Style on a Budget with Cheap Kilts

- Unleashing Style and Functionality | Exploring Tactical Kilts

- Mangalore’s Heroic Lady marks 105th Birthday

- Santa the Christmas spirit

- Geriatric care: Mangalore strikes a fine balance

- The Don Who Made Two Empires to Clash

- CHITRAPUR SARASWATS - A Great Kanara Community

- Our new President Ram Nath Kovind’s significant journey to Rashtrapathi Bhavan

- Marriages made in heaven, big fat weddings made in India

- Eid insight - The giver of glad tidings

- CITY INFORMATION

- TRAVEL

- TOURIST INFORMATION

- HEALTH CARE

- MISCELLANEOUS

Write Comment

Write Comment E-Mail To a Friend

E-Mail To a Friend Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter  Print

Print