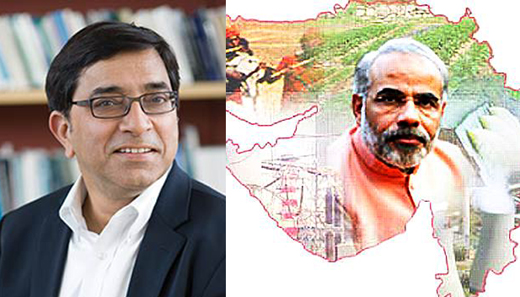

How damaging are Narendra Modi’s historical lapses?

How damaging are Narendra Modi’s historical lapses?

mangaloretoday.com / NDTV

February 06, 2014: Ashutosh Varshney is Sol Goldman Professor of International Studies and the Social Sciences and director of the India Initiative at Brown University. He is the author, most recently, of Battles Half Won: India’s Improbable Democracy (Penguin).

It has been repeatedly observed that Narendra Modi’s recalling of Indian history is imprecise. In Patna, he said Takshashila was in Bihar; it is in Pakistan. He also said Porus was defeated on the banks of the Ganga; that battle with Alexander never went beyond the Jhelum river in Pakistani Punjab.

In Meerut earlier this week, he argued that the Congress party had thoroughly devalued India’s first war of independence, which began in Meerut. The Congress did so because it could not possibly take credit for the bravery of the fighters of a pre-Congress era. The Congress, after all, was born in 1885; and the rebellion against the British erupted nearly three decades before that - in 1857.

There is considerable historical inaccuracy here. In The Discovery of India, Jawaharalal Nehru celebrates the indomitable spirit of Indian fighters in 1857, especially "Lakshmi Bai, the Rani of Jhansi, a girl twenty years of age, who died fighting".

On how to characterize the 1857 rebellion, too, there is partial, if not full, agreement between Nehru and Modi. Nehru sees elements of nationalism in the rebellion. However, consistent with the modern theory of nationalism, he calls it "essentially a feudal rising, though there were some nationalistic elements in it". "It was much more than a military mutiny, and it spread rapidly and assumed the character of .. a war of Indian Independence." But it is "due to the abstention or active help of the (Indian) princes", says Nehru, "that the British succeeded in crushing" the revolt.

There was no rebellion in Western and Southern India. The 1857 revolt was confined to the North and the East. Finally, mass support for the rebellion was in doubt beyond Delhi and some parts of modern-day UP. Hence the Nehruvian claim that the 1857 revolt was only in part a war of independence. It just can’t be compared to the full-blown freedom movement in the first half of the 20th century.

In 1957, Nehru as Prime Minister also celebrated the centenary of 1857, making a famous speech at the Ramlila Maidan. Given the paucity of Indian accounts of the rebellion, new scholarly works too were commissioned.

Modi clearly has not read The Discovery of India, nor is he familiar with Nehru’s 1957 speech.

But are these historical inaccuracies damning? This, of course, is the much larger question. And here the distinction between history and heritage is critical. What does this distinction imply?

Consider Kerala’s Christianity. In a heritage-based conception, many Kerala Christians argue that St. Thomas, the apostle of Jesus, brought Christianity to Kerala as early as 50 AD. Historians have not been fully able to establish the veracity of this belief. The believer goes on undeterred.

One of the best known examples of the distinction between history and heritage comes from Sri Lanka. In Charred Lullabies, Valentine Daniel, an anthropologist at Columbia University, famously argues that the Tamil conception of their place in Sri Lanka is driven by the idea of heritage, whereas the dominant Sinhala conception is historical, depicting in chronological detail how the Sinhalese are the original inhabitants of the island. The two conceptions fatally clashed in Sri Lanka, though that does not have to be the case universally.

On the whole, nationalist politicians have rarely been exemplary historians, known for fidelity to facts. Rather, they selectively retrieve from history - to create a narrative that is politically usable. Modi is no exception. He is trying to craft a narrative which can show him as championing his own idea of India and making it stick with the masses. He is not in politics to please the scholar and the historian. He is an ideological trailblazer, seeking to win popular affection.

- Need For ‘Students, Alcohol and Drugs’ survey

- New Synthetic Drugs Trapping Youth

- Mood Modifying Chips - Future of Drug Use

- Ramping up Indo-Bangla border security

- IITM- A premier educational Institution in a forest. What can we learn?

- Former PM, Manmohan Singh: Notable laws passed under his tenure

- Hashish on Ratnagiri Seashore

- The Poor cry out to Us: Do we respond?

- Clandestine Meth Labs Sprouting Across India

- Hydro ganja from Bangkok latest craze among youth in India

- "Memories to Treasure" Dr.Michael Lobo’s new book

- Dominance of Private Universities: Will it make education inaccessible to underprivileged students?

- Monti Phest: A rich heritage of South Canara

- Kashmir Bhavan in Bengaluru: A must visit place

- "MAI and I" Book of Angelic Emotions

- Draupadi Murmu - The New ’President of India’

- Anthony Ashram in the city grows a classic museum

- First College of Fisheries in India - A Golden Jubilarian

- Flushing Meadows - A Vintage Mansion

- The Colonel�s Bequest

- A Mangalorean PM and his RBI Governor Brother: The Extraordinary story of the Benegal Brothers

- There is no higher religion than Truth: Theosophical Society

- L�affaire - Ashu & Yiju of Mangalore

- Mangalore in Kowloon

- 1568 to 2018 AD: 450 years of Christianity in Mangaluru

- Vice President elect Naidu moves on from nadir to zenith, the phenomenal journey

- Embracing the Outdoors: How Heated Jackets Are Revolutionizing Cold Weather Activities

- Efficient and Sustainable Packaging Solutions with FIBCs

- The Hybrid Kilt Revolution | Where Tradition Gets Trendy

- Affordable Elegance | Embrace Style on a Budget with Cheap Kilts

- Unleashing Style and Functionality | Exploring Tactical Kilts

- Mangalore’s Heroic Lady marks 105th Birthday

- Santa the Christmas spirit

- Geriatric care: Mangalore strikes a fine balance

- The Don Who Made Two Empires to Clash

- CHITRAPUR SARASWATS - A Great Kanara Community

- Our new President Ram Nath Kovind’s significant journey to Rashtrapathi Bhavan

- Marriages made in heaven, big fat weddings made in India

- Eid insight - The giver of glad tidings

- CITY INFORMATION

- TRAVEL

- TOURIST INFORMATION

- HEALTH CARE

- MISCELLANEOUS

Write Comment

Write Comment E-Mail To a Friend

E-Mail To a Friend Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter  Print

Print