Revisiting the Mahatma

Revisiting the Mahatma

Mangalore Today News Network

By Mahesh Nayak

Mangaluru, January 29, 2019: On 2nd October 1869 was born one of the greatest leaders of the 20th Century, the man who was destined become the Father of our Nation and to be hailed throughout the world as an Apostle of Peace. Yes, we are speaking about Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who is known to the world only as ‘Mahatma Gandhi’. This year marks the 150th birth anniversary year of the Mahatma and celebrations galore are planned across the country to pay tribute to the noble soul. As we salute his extraordinary personality, it is worthwhile to review his life and times and critically evaluate the principles that he lived for.

Mangaluru, January 29, 2019: On 2nd October 1869 was born one of the greatest leaders of the 20th Century, the man who was destined become the Father of our Nation and to be hailed throughout the world as an Apostle of Peace. Yes, we are speaking about Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who is known to the world only as ‘Mahatma Gandhi’. This year marks the 150th birth anniversary year of the Mahatma and celebrations galore are planned across the country to pay tribute to the noble soul. As we salute his extraordinary personality, it is worthwhile to review his life and times and critically evaluate the principles that he lived for.

Mahatma Gandhi will always enjoy a stellar role in history as the iconic leader of the Indian Freedom Movement. But his greater intangible achievement has been to impart the freedom struggle with the ideal of non-violence and thereby deeply embed the value into our national psyche. His concept of Ahimsa, or non violent struggle, has become the preeminent symbol of India’s long march to Independence and similar movements across the globe, such as in South Africa.

So far as ideas are concerned, people all over the world identify India more easily with non-violence than perhaps with anything else. Though Gandhiji is hailed for being a passionate advocate of peaceful action, there are also those who critique him and his methods. Today, when the world is witnessing unprecedented levels of violence in the form of crime, terrorism, regional and global conflict, the question naturally arises: Is the Gandhian principle of non violence relevant today?

It is often argued by those who are cynical of Gandhi’s methods that today we live in a technologically advanced world which bears unimaginable destructive potential and an almost unlimited capability to inflect harm. They postulate that modern threats to peace should be confronted with matching use of force and not with old world values and feel good tactics. During his lifetime Mahatma Gandhi himself was accustomed to such criticism as many considered his ideas to be Utopian even in those days. To them his response was simple: “An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.”

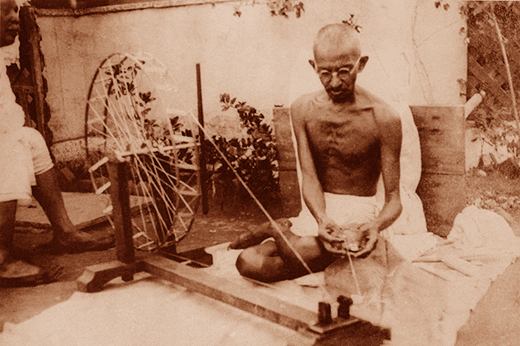

Despite the constant criticism, Gandhiji’s philosophy of nonviolence has continued to survive, thereby drawing attention to its own immortality. The reason for its everlasting value can be better understood if we explore its deep roots. Mahatma Gandhi developed his belief in non-violence long before he became involved with the Freedom Struggle in India. It was during the 21 years that he spent in South Africa that the outrage that he felt over the racist humiliation inflicted upon him by the State made him to react and take up the cause of fighting against oppression.

In this fight, he recognized non-violence as a worthy tool to be employed – one which would instantly give a moral edge to his cause. In pursuing non violence, Mahatma Gandhi drew deeply from India’s age old traditions which worshipped Ahimsa as an ideal in life. Ahimsa – or nonviolence – is one of the cardinal virtues and an important tenet of all ancient Indian faiths such as Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism.  Furthermore, Gandhiji was profoundly influenced by his personal correspondence with Leo Tolstoy, the Great Russian thinker and humanist. Already a legendary literary giant in his own right, Leo Tolstoy shared Mahatma Gandhi’s anger against oppression inflicted by an unfair state and they exchanged ideas freely through the numerous letters that they wrote to each other for several years.

Furthermore, Gandhiji was profoundly influenced by his personal correspondence with Leo Tolstoy, the Great Russian thinker and humanist. Already a legendary literary giant in his own right, Leo Tolstoy shared Mahatma Gandhi’s anger against oppression inflicted by an unfair state and they exchanged ideas freely through the numerous letters that they wrote to each other for several years.

During his lifetime, Leo Tolstoy had fought primarily against the Orthodox Church and the Russian State. In both cases, his main opposition was for what he considered to be their deviation from the original teachings of Jesus Christ. Tolstoy located the answers to his anguish for humanity’s future in The Sermon on the Mount and this in turn influenced Mahatma Gandhi with the compassionate message of Jesus Christ. Gandhiji, who was already influenced by the age old Indian concept of Ahimsa, saw his inclinations bolstered by the Russian litterateur’s passionate review of the Sermon on the Mount, in which Jesus call the pacifiers, the sons of God.

Then again during a period of imprisonment in South Africa, Gandhiji read the essay ‘Civil Disobedience’ by Henry David Thoreau, a 19th-century American thinker and one of the protégés of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Thoreau had absorbed Indian philosophy. His writings influenced Mahatma Gandhi greatly and he adopted the term ‘civil disobedience’ to describe his strategy of non-violently refusing to cooperate with injustice. In doing so, Gandhiji chose to substitute the term with the Sanskrit word Satyagraha which means ‘devotion to truth’. Hence Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of non-violence was not a fancy idea that he caught on a whim, but rather it was a product of a deep understanding of human nature and a solid philosophic foundation sourced from the best ideas in the world.

One of the important reasons that Gandhiji adopted the principle of non violence was that he understood the cyclical nature of pain which perpetuates the misery of humankind. When we are deliberately hurt by another human being, it gives rise in us to an animalistic urge to hit back and return the hurt with interest. Extracting revenge gives us the satisfaction that justice has been done. This initiates a never ending tit for tat, which is both destructive and self defeating as it can conclude only when one of the parties is no more standing.

On the other hand, most of the hurt that we endure comes from those who are more powerful than us and this puts us in a disadvantageous position, whereby we cannot fulfill our much desired need for revenge. In such cases, we unconsciously look for an outlet in the form a person who is weaker than us, upon who we can unload our frustration. When this happens, the victim who is too weak to retaliate against us also suffers a similar predicament as we had originally faced and will find a still weaker victim to pass on the hurt. Here too a vicious and never ending cycle is triggered, of hurt breeding more hurt. In popular psychology this tendency to gain personal relief by passing on our pain to others is known as ‘transfer of pain’. Many criminal modes of behaviour and the prevalence of sadistic practices such as ragging in college hostels are sourced to this phenomenon.

Bertrand Russell, the great British philosopher, best illustrated this phenomenon with an example. In his book, Education and the Social Order, he writes: “I found one day in school a boy of medium size ill- treating a smaller boy. I expostulated, but he replied: ‘The bigs hit me, so I hit the babies; that’s fair.’ In these words he epitomized the history of the human race.” Hence the blame for the long and very violent history of mankind can largely be placed on this anomaly in human nature.

Pain serves the evolutionary purpose of warning us of danger to our well being. It is a stimulus to be recognized and acted upon in such a way that the original causative factors of pain are identified and solved using rational means. Mahatma Gandhi instinctively understood this fact and wanted to protect our country from the devastating fallout of transfer of pain. He knew that if real peace had to follow after Independence, the country had to be free from all negative influences. First of all the chain of cyclical violence and perpetual transfer of pain from people to people and generation to generation had to be stopped.

The concept of Ahimsa or non-violence provided the perfect solution. A concept based on nonviolence in thought, word and action. It is often pointed out that verbal violence is worse than physical violence. The bodily pain is soon forgotten, but words that hurt stick in our minds forever. Emotional pain is indeed more powerful than physical pain.

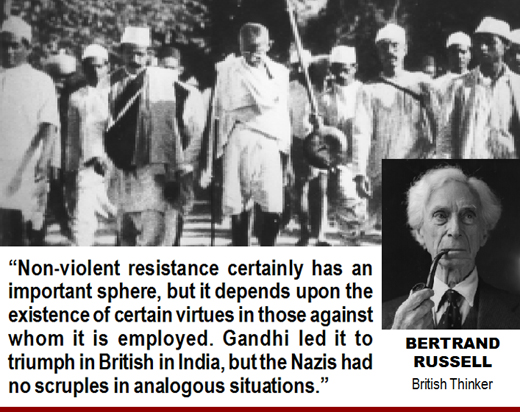

So is the Gandhian principle of non violence relevant today? There are many who dispute Gandhiji’s views. One of those who were not fully convinced with the Gandhian method was Bertrand Russell, who I have referred to earlier. Russell himself detested violence and was a self declared pacifist. He had undergone six months of imprisonment during the First World War for his open opposition to the Great War. He elaborated his views on the Gandhian Method with typical clarity in his autobiography. To quote him, he says: “Non-violent resistance certainly has an important sphere; as against the British in India, Gandhi led it to triumph. But it depends upon the existence of certain virtues in those against whom it is employed. When Indians lay down on railways, and challenged the authorities to crush them under trains, the British found such cruelty intolerable. But the Nazis had no scruples in analogous situations.”

While acknowledging the effectiveness of Gandhi’s strategy, this insightful observation of Bertrand Russell also highlights the limitations it poses. It is true that non-violence could be totally ineffective when pitted against an unsympathetic adversary, be it a hungry beast or an ogre in human form, such as those among the Nazis of Hitler’s Germany.

Speaking on another tangent, we have scores of revolutionaries who believe in pursuing the righteous path through violence. They believe in the language of the gun and consider armed resistance as the only way to gain liberation for their pet causes. Such movements, where they have succeeded, it has been at a great cost. And the cost has continued beyond achieving their original goals and made peace something to be purchased on a daily basis, with continuation of aggressive policies. In all such cases non-violence offers immense scope in terms of more creative and refined approaches to connect with the adversary. It must be remembered here that to Gandhi, non-violence was not passive yielding to subjugation, but rather an active resistance to objectionable practices using harmless means. The basic objective was to create a human connection.

Nonviolence as a strategy invokes the highest level of civility, while communicating a very human message all too easy to put across. It implies intelligent and understanding response rather than the use of brute force. “At the center of non-violence stands the principle of love,” said Martin Luther King, Junior, the famous American civil rights activist and an ardent Gandhian himself. Mahatma Gandhi, by infusing our national character with the value of non-violence, has given a real meaning to our freedom. If our country had won independence through harsh methods, our subsequent history too would have been equally harsh as all our energy and creativity would have been lost in maintaining a fragile peace. By relying on nonviolence and enabling peace, he has laid the foundation for our country’s talent to bloom.

The freedom that we have gained through non-violent methods has brought lasting peace because it is both natural and intrinsic to our character. The peace thus derived had provided the young nation with the required stability and made democracy and all round progress practical and viable. Today not a day passes, when we do not come across a street demonstration, a bandh or a hunger strike for perpetuating a variety of causes. All these are but peaceful manifestations of the Gandhian Method in the common man’s life. It is the first choice of action for any aggrieved people anywhere in India.

So, the answer to our question is a resounding ‘Yes’. Gandhian non violence continues to be relevant each and every day. If are experiencing any negativity these days, it is not because Gandhian ideals are no longer relevant, but more so because we have strayed from them. Hence it is time for the younger generation to understand Gandhiji and take his ideals forward with a new relevance which suits modern times. In this, the 150th year after Mahatma Gandhi’s birth, let us honour his memory with a renewed commitment to non-violence and peace.

- Need For ‘Students, Alcohol and Drugs’ survey

- New Synthetic Drugs Trapping Youth

- Mood Modifying Chips - Future of Drug Use

- Ramping up Indo-Bangla border security

- IITM- A premier educational Institution in a forest. What can we learn?

- Former PM, Manmohan Singh: Notable laws passed under his tenure

- Hashish on Ratnagiri Seashore

- The Poor cry out to Us: Do we respond?

- Clandestine Meth Labs Sprouting Across India

- Hydro ganja from Bangkok latest craze among youth in India

- "Memories to Treasure" Dr.Michael Lobo’s new book

- Dominance of Private Universities: Will it make education inaccessible to underprivileged students?

- Monti Phest: A rich heritage of South Canara

- Kashmir Bhavan in Bengaluru: A must visit place

- "MAI and I" Book of Angelic Emotions

- Draupadi Murmu - The New ’President of India’

- Anthony Ashram in the city grows a classic museum

- First College of Fisheries in India - A Golden Jubilarian

- Flushing Meadows - A Vintage Mansion

- The Colonel�s Bequest

- A Mangalorean PM and his RBI Governor Brother: The Extraordinary story of the Benegal Brothers

- There is no higher religion than Truth: Theosophical Society

- L�affaire - Ashu & Yiju of Mangalore

- Mangalore in Kowloon

- 1568 to 2018 AD: 450 years of Christianity in Mangaluru

- Vice President elect Naidu moves on from nadir to zenith, the phenomenal journey

- Embracing the Outdoors: How Heated Jackets Are Revolutionizing Cold Weather Activities

- Efficient and Sustainable Packaging Solutions with FIBCs

- The Hybrid Kilt Revolution | Where Tradition Gets Trendy

- Affordable Elegance | Embrace Style on a Budget with Cheap Kilts

- Unleashing Style and Functionality | Exploring Tactical Kilts

- Mangalore’s Heroic Lady marks 105th Birthday

- Santa the Christmas spirit

- Geriatric care: Mangalore strikes a fine balance

- The Don Who Made Two Empires to Clash

- CHITRAPUR SARASWATS - A Great Kanara Community

- Our new President Ram Nath Kovind’s significant journey to Rashtrapathi Bhavan

- Marriages made in heaven, big fat weddings made in India

- Eid insight - The giver of glad tidings

- CITY INFORMATION

- TRAVEL

- TOURIST INFORMATION

- HEALTH CARE

- MISCELLANEOUS

Write Comment

Write Comment E-Mail To a Friend

E-Mail To a Friend Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter  Print

Print